Picture this:

A man storms into a wedding, drags the bride away, and declares his undying love. The guests gasp. The music swells. The audience? Applauds his passion.

A hero breaks bones, burns bridges, and bulldozes through moral lines, all in the name of justice. The audience? Whistles in approval.

A woman hesitates before saying ‘yes’. The hero takes it as a challenge, stalking, harassing, and manipulating her until she finally “falls in love.” The audience? Call it destiny.

Cinema is our grand storyteller, our mythmaker, our mirror. Except that, sometimes the mirror reflects a version of ourselves we should be questioning and not celebrating.

Across languages and industries, Indian films have a dangerous habit of glorifying the very things we should be rejecting. Possessiveness as love, Aggression as strength, Violence as justice, and Stalking as romance.

Why does Indian cinema keep feeding us such narratives of toxic masculinity, romanticized abuse, and glorified violence, wrapped up in whistle-worthy dialogues and foot-tapping dance numbers?

Because more than the majority of the audience love it! Involuntarily!

1. The Hero Who Can Do No Wrong (Even When He Does EVERYTHING Wrong).

What makes a hero, heroic?

From brooding, alcoholic “lovers” to law-breaking “vigilantes,” our heroes can wreck lives, cross boundaries and still walk away with zero consequences.

- Kabir Singh (Hindi) – Toxic, violent, entitled, but we’re told he’s just madly in love.

- Arjun Reddy (Telugu) – The same story, but with more aggression and even less accountability.

- Vikram Vedha (Tamil/Hindi) – A criminal, but with enough swagger to make us forget his crimes.

Indian cinema has a fixed formula for male protagonists. Such as an angry, broody, hyper-masculine man who asserts dominance over everyone, including his love interest. His aggression isn’t treated as a flaw but as evidence of his strength and passion. The best part? No matter how horrible these men act, the film will always bend reality to justify them.

If they drink, it’s because they’re heartbroken.

If they kill, it’s because they had no choice.

If they slap a woman, it’s because they love her too much.

It convinces audiences that the hero is above morality, above law and above consequences.

And just like that, aggression becomes strength and red flags become romantic. Especially when the hero’s flaws are balanced either by a tragic backstory, a villain who’s “worse,” or by the heroine herself, who magically “fixes” him by the end of the film.

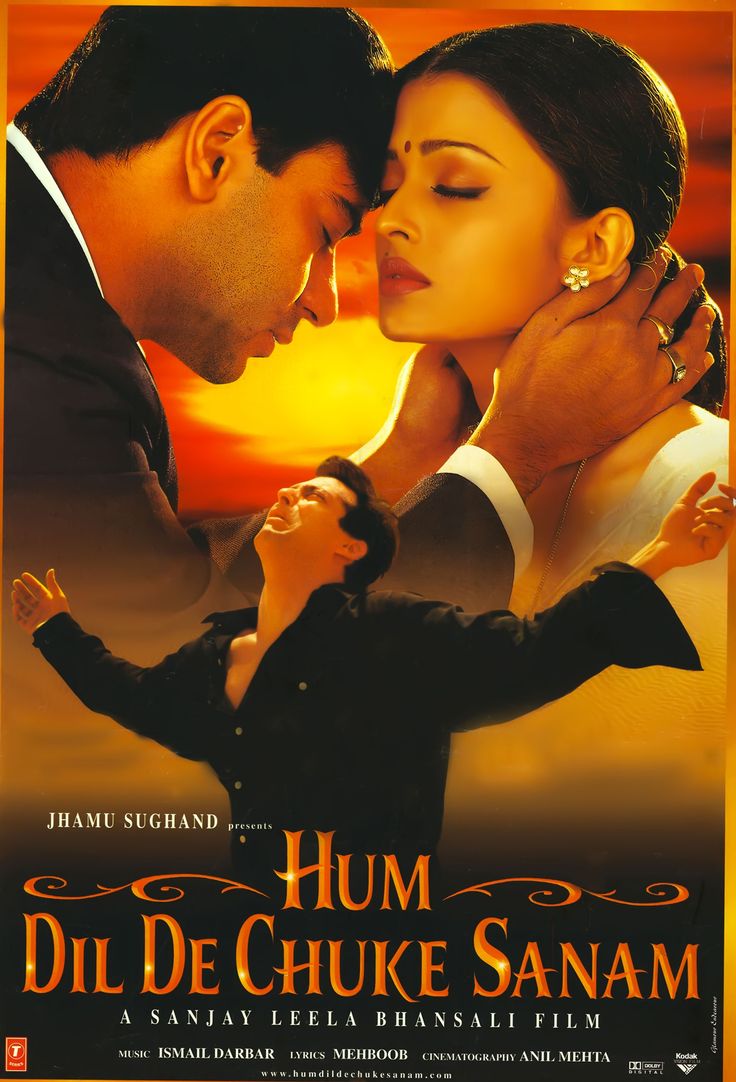

2. Stalking, Obsession and Manipulation = “True Love” (Apparently!)

Let’s set the record straight: Stalking isn’t love. Harassment isn’t persistence. No means NO.

Yet, Indian cinema keeps selling us the same tired script. It often showcases a woman’s rejection as an invitation to try harder.

Romantic plots thus begin with:

A man following a woman everywhere.

Manipulating her into spending time with him.

Controlling her choices, friendships, and career decisions even (romantically as the script says).

Making aggressive, borderline criminal gestures to “prove” his love.

The problem? These behaviors aren’t framed as harassment, they’re framed as ‘persistence.’ And the heroine eventually “falls for him,” making the audience believe that stalking is a valid way to win love.

- Raanjhanaa (Hindi) – The hero stalks a girl for years, guilt-trips her, and even harms himself to gain her love.

- Remo (Tamil) – The hero disguises himself as a nurse to trick a woman into loving him.

These narratives have real-life consequences. It normalizes toxic relationships and conditions men to believe that women secretly enjoy being pursued aggressively.

3. The Disposable Woman: Built for Love, Tears, and Tragedy

If women in Indian cinema had a job description, it would go like this:

“Wanted: Female lead. Must be beautiful, submissive, and ready to die for the hero’s character development. Depth is not required.”

Whether it’s a masala blockbuster or a deep emotional drama, women exist as props, not people. Despite the increasing presence of strong female voices in filmmaking, mainstream Indian cinema still struggles to give women meaningful roles.

The heroine is rarely an independent character with her own ambitions. Instead, she exists to:

Serve as the love interest—her story revolves around the hero’s journey.

Be a moral compass—her role is to tame the “wild” hero.

Provide visual appeal—her presence is often reduced to glamour and dance sequences.

- Ghajini (Tamil/Hindi) – The heroine is brutally murdered just so the hero can have a revenge arc.

- Ala Vaikunthapurramuloo (Telugu) – The heroine exists purely for the song sequences and smiles.

- Singham (Hindi) – A high-octane cop drama where the only thing the heroine polices is her saree pleats.

- Brahmastra (Hindi) – How can we forget about this wasted talent who uttered a hundred ‘Shivaa..’ just to exist throughout the script.

When a female character does show ambition, the film often punishes her for it. Women who prioritize their careers over relationships are frequently portrayed as selfish, unlikable, or in need of a reality check.

The result? A generation of female viewers fed the idea that their worth is tied to their relationships, not their individuality.

4. Why Talk It Out When You Can Just Kill Everyone?

One thing Indian heroes hate? Paperwork.

Why waste time with lawyers and police when you can single-handedly eliminate the bad guys in slow motion?

- KGF (Kannada) – One man versus an entire criminal empire. No laws, just lots of bullets.

- Pushpa (Telugu) – Smuggling, brutality, and violence, packaged as mass entertainment.

- Bheeshma Parvam (Malayalam) – A crime lord presented as a noble savior.

But here’s the problem. When violence becomes entertainment, real-life brutality stops shocking us. Instead of promoting conversations, negotiations or systemic change, these films promote individual violence as the ultimate solution.

Should we really be celebrating heroes who solve everything with their fists?

5. The Convenient Villain: Who’s the “Bad Guy” This Time?

Apart from glorifying the heroes, we also choose who to demonize.

Religious minorities? Often the villain.

LGBTQ+ characters? A joke, or worse, a horror element.

Dark-skinned people? Cast as either the criminal or the comic relief.

- Kanchana (Tamil/Telugu) – A transgender character used for horror.

- Sadak 2 (Hindi) – Stereotypes wrapped in lazy villain tropes.

- Sura (Tamil) – Racist comedy disguised as “harmless fun.”

And we rarely question it. Cinema has the power to shape perceptions. When filmmakers rely on these lazy stereotypes, they actively contribute to discrimination in society.

Why Do We Keep Watching These Films?

If these toxic elements are so common, why do audiences continue to support them?

- Box Office Success > Social Responsibility – Filmmakers prioritize profits over ethics.

- “It’s Just Entertainment” Excuse – People dismiss criticism, claiming “it’s just a movie.”

- Fan Culture – Superstars have such loyal fanbases that their films succeed no matter what they promote.

- Cultural Conditioning – We’ve seen these tropes for decades, so they feel “normal.”

The truth is, films influence real life. Audiences may not always consciously absorb these toxic messages, but they subconsciously shape behaviors, expectations, and societal norms.

Is Change Finally Coming?

Absolutely. Not all movies are stuck in the past. Some filmmakers are pushing back against these outdated tropes. We have makers who are experimenting with progressive, layered storytelling, breaking stereotypes, and redefining heroes.

- Thappad (Hindi) – Calls out normalized domestic violence.

- Super Deluxe (Tamil) – A fresh take on LGBTQ+ representation.

- The Great Indian Kitchen (Malayalam) – Exposes patriarchy within households.

- Article 15 (Hindi) – Addresses caste discrimination.

- Gargi (Tamil) – A woman-centric legal drama challenging the system.

These films prove that entertainment doesn’t have to be regressive. Audiences deserve stories that inspire, challenge, and reflect a more evolved society.

Final Thought: Will We Keep Clapping for Toxicity?

Cinema isn’t just a mirror of society, it’s also a tool to change it.

So, what do we want? More of the same toxic narratives, or films that break the cycle and push us forward?

Change begins with us—the audience. If we start questioning and rejecting toxic storytelling, filmmakers will have no choice but to evolve.

It’s time to ask ourselves: Are we ready to demand better stories?